Germany-Kenya Skilled Worker Deal: Brain Drain or Win-Win?

Do the Negatives Outweigh the Positives in Such Deals or Not?

In 1898, Kwegyir Aggrey, a budding African intellectual already studying Latin and Greek in colonial Gold Coast (now Ghana), was selected to be trained as a missionary in the US. His intellect had caught the attention of the colonial masters, and on 10 July, he left Gold Coast to attend Livingstone College.

He studied various subjects, graduated with three academic degrees, and by 1903, began teaching at Livingstone (his alma mater). This is just one example of African brain drain in the 1900s. It didn’t cause as much uproar then because most of these intellectuals eventually returned to the continent.

Kwegyir Aggrey, for instance, returned to Africa in 1920 to conduct a research expedition on improving education on the continent. He visited, collected, and analyzed data in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Cameroon, and his home country, Ghana.

There, he gave a powerful speech that persuaded the governor to change the system of Achimota College from single-gender (male students) to co-educational (male and female students). He echoed a quote often attributed to Charles McIver:

“The surest way to keep people down is to educate the men and neglect the women. If you educate a man, you simply educate an individual, but if you educate a woman, you educate a whole nation."

Achimota College went on to become the University of Ghana, one of the most prestigious universities in the continent.

A win-win situation if there ever was one. Is that still the case today when such deals happen in Africa?

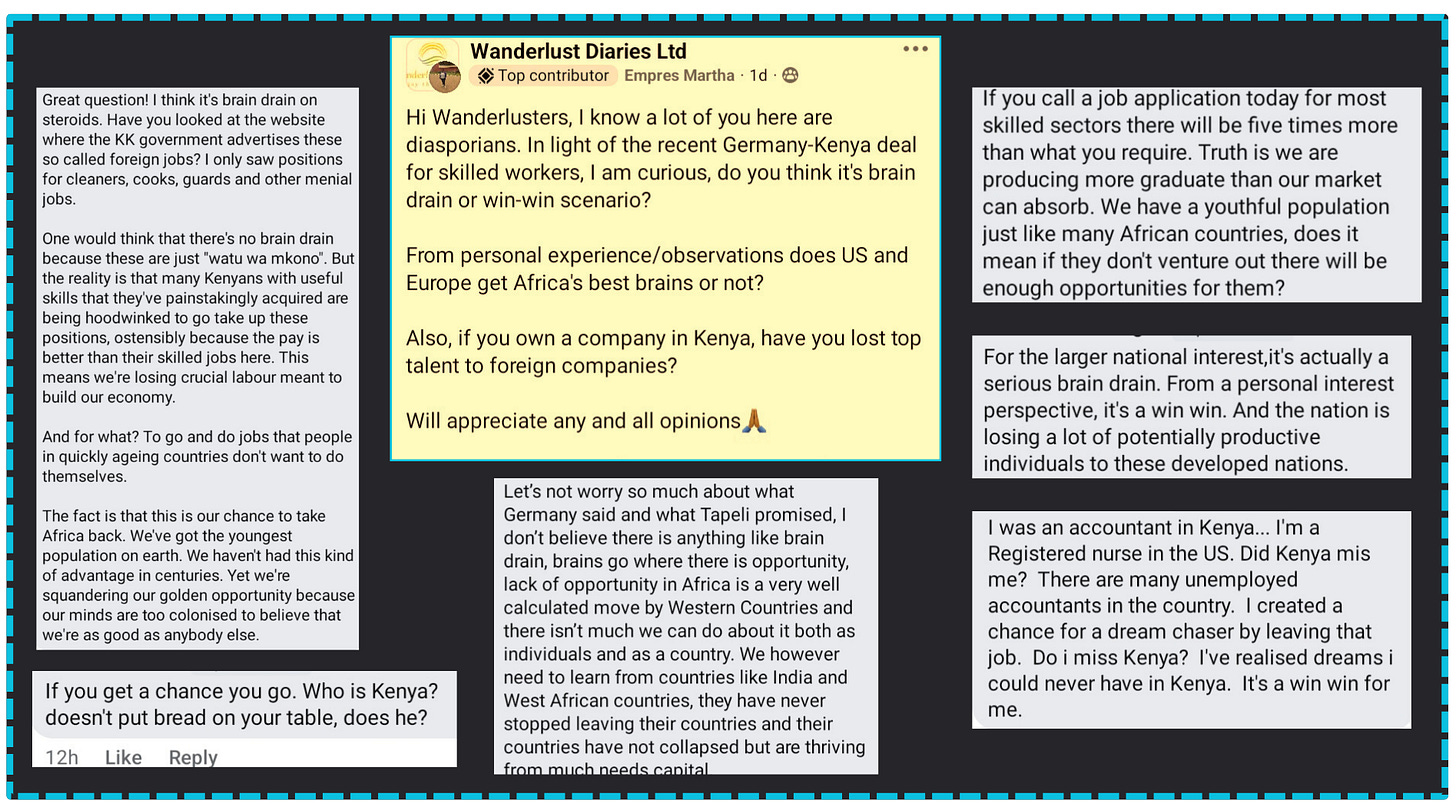

To investigate, I asked the question on Wanderlust Diaries Ltd—a popular travel and diaspora Facebook group in Kenya. The answers were as varied as they were interesting, but this response stuck out.

“If you get a chance to go, go. Who is Kenya? Doesn’t put bread on your table, does he?”

That is the crux of it, no? At an individual level, the benefits are indisputable. More so, the respondent is right in questioning why the needs of a nation should transcend those of an individual.

When you think about it, the development of Kenya or Tanzania matters only because it affects the development of individual Kenyans or Tanzanians.

A paper published by the African Development Bank in 2008, “Is the Brain Good for Africa,” agrees with this take, noting that the costs and benefits of brain drain should be viewed from the perspective of individuals.

“The gains to the migrants themselves and their families who receive indirect utility and remittances more than offset the losses of the brain drain. According to one of our calculations, the present value of remittances more than covers the cost of educating a brain drainer in the source country.” The paper says.

That’s a fair analysis, but a seminal paper by Maurice Schiff negates this take. Schiff argues that brain drain is unambiguously larger than any gain.

He further notes that even if those who migrate invest in education back home, the average ability of the newly educated will be lower because skills are heterogeneous (of different origins; not the same), and individuals who migrate tend to have exceptional skills that are impossible to recreate.

That’s also a balanced view. So, now what?

With such varying positions, all equally backed by research, not to mention all the other studies showing that in the face of skilled migration, the needs of a nation as an entity matter too, how do we determine if the Germany-Kenya deal and other such deals in the continent are a brain drain or win-win?

Empirical data is a good place to start because numbers do not lie.

Statistics on Skilled Migration from Africa to OECD Countries

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a forum of 37 highly developed economies collaborating to promote sustainable economic growth.

According to the organization’s data, Africa is the fourth and fifth highest supplier of total (16.6%) and skilled immigrants (14.7%) to OECD countries, respectively.

That might not seem very high, but it hides a heartbreaking context—Africa is the least educated region in the world. Only 9.4% of Africans enroll for tertiary education, way below the global average of 38%. With such a low enrollment rate, the continent desperately needs to hold on to its few skilled individuals.

Furthermore, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which has lower education rates than North Africa, is overrepresented in global skilled migration. SSA accounts for 9.6% of global skilled migration and 7.6% of global unskilled migration.

In contrast, North Africa accounts for 5.1% of global skilled migration and 9.6% of global unskilled migration.

With those numbers in mind, let’s take a minute to analyze some of the findings in the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) paper published in 2020 on “African countries and the brain drain: Winners or losers? Beyond remittances”

The paper is a work in progress. It analyzes data up to 2015 because that’s when it was first available. Here is a summary of the results.

The most interesting tidbit is that North Africa managed to reverse its brain drain losses. That means the gains the region gets from the skilled North Africans who migrate surpass the losses.

It might be interesting, but it is not unexpected. Didn’t we see from the numbers that North Africa exports more unskilled people to the OECD countries (9.6%) than skilled ones (5.1%)? The reversal happened because the region found a way to hold on to its skilled population.

As for Sub-Saharan Africa, especially East and West Africa, where the bulk of skilled migrants to OECD countries come from, brain drain loss is trending upwards.

As a Sub-Saharan African looking to migrate or one living in the diaspora, you might be tempted to shrug and say, “Why should I care?”

After all, your family is living well, and you are making or will make a home in the UK, the US, or whichever country you migrate to. Please consider these two reasons.

Your Home Country Cannot Kick You Out: Did You See that Sweden is Willing to Offer Migrants $34,000 to Return Home?

This is not meant to criticize Sweden. It is their country, and they are entitled to develop policies that benefit them. In a press conference early this month, Migration Minister Johann Forsell told journalists that Sweden was in the middle of a paradigm shift in its migration policy.

He said the driving factor is that migrants are straining Sweden's cradle-to-grave welfare system (a system where many public services, such as education, are free but funded by taxes). Whether that is the real reason, who knows?

Of greater importance is that Sweden is not the only European country that has a scheme to pay migrants to return home. Germany, France, Norway, and Denmark all have similar schemes. This is a recent development, with many European countries now embracing a hard stance on immigration.

As an African immigrant, what happens in the future if you are asked, even paid, to leave?

It is true that Kenya, Tanzania, or Nigeria, as entities, cannot put food on your table.

But only your home country cannot kick you out when it is all said and done. It is upon every African to ensure African countries work so that you can always return when you need to (or only leave because you want to, not because you are desperate).

The Skills You Learn in the Diaspora Will Not Translate if Africa Continues to Invest So Little in R&D

When Spice FM interviewed Roseline Njogu, the Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs in Kenya, about the Germany-Kenya deal, she explained that the biggest benefit was the transfer of skills and technology.

She used the example of the automotive industry—that when Kenyans go to Germany and work in the highly regarded automotive industry, in 15 years or so, they would return to the country (hopefully) and help the Kenyan automotive sector grow by investing in it.

That sounds good, huh? Here is the thing: Kenya and Africa invest so little in R&D that finding a conducive automotive environment for these individuals to invest in is next to impossible. Look at what happened to Mobius—the only car manufacturer in Kenya.

The company shut down after the government imposed a tax bill of 85.74 million Kenya Shillings. Who would want to invest in an industry where the government would rather see you shut down than work with you to nurture the fledgling automotive industry?

You should care because when you are finally ready to return (or are chased out 🤭), you will need a country that can accommodate the skills you learned in the diaspora.

Final Word

The question was, are skilled worker migrant deals win-win or brain drain?

This discussion has proven that brain drain is a win-win situation at the individual level but a lose-lose situation at the country level. The trick is to find the balance.

Countries should invest in R&D and education and nurture a culture of entrepreneurship to retain their highly skilled citizens. They should also not make deals that disadvantage the country and drive up the brain drain.

At the same time, individuals who choose to migrate should care enough about the state of their home country to advocate for efforts that reduce brain drain.

More than that, for the African Continental Free Trade Area to work and produce the promised gains, Africa desperately needs to retain its highly skilled people. We once argued in this newsletter that Africa’s new oil is its people's genius, talent, and ambition.

That has not changed and needs to be nurtured.

Thank you for reading Africa: Not an Afterthought.

We lead the conversation on how Africa can leverage Technology, Trade (AfCFTA), Regional Integration and Pan-Africanism to build a continent that is no longer an afterthought.

Kindly:

This is a great article. I love the point at the end: Africa’s greatest resource is its people. Without nurturing our people, all of our toted natural resources will go to waste. Or simply continue to be exploited by others.